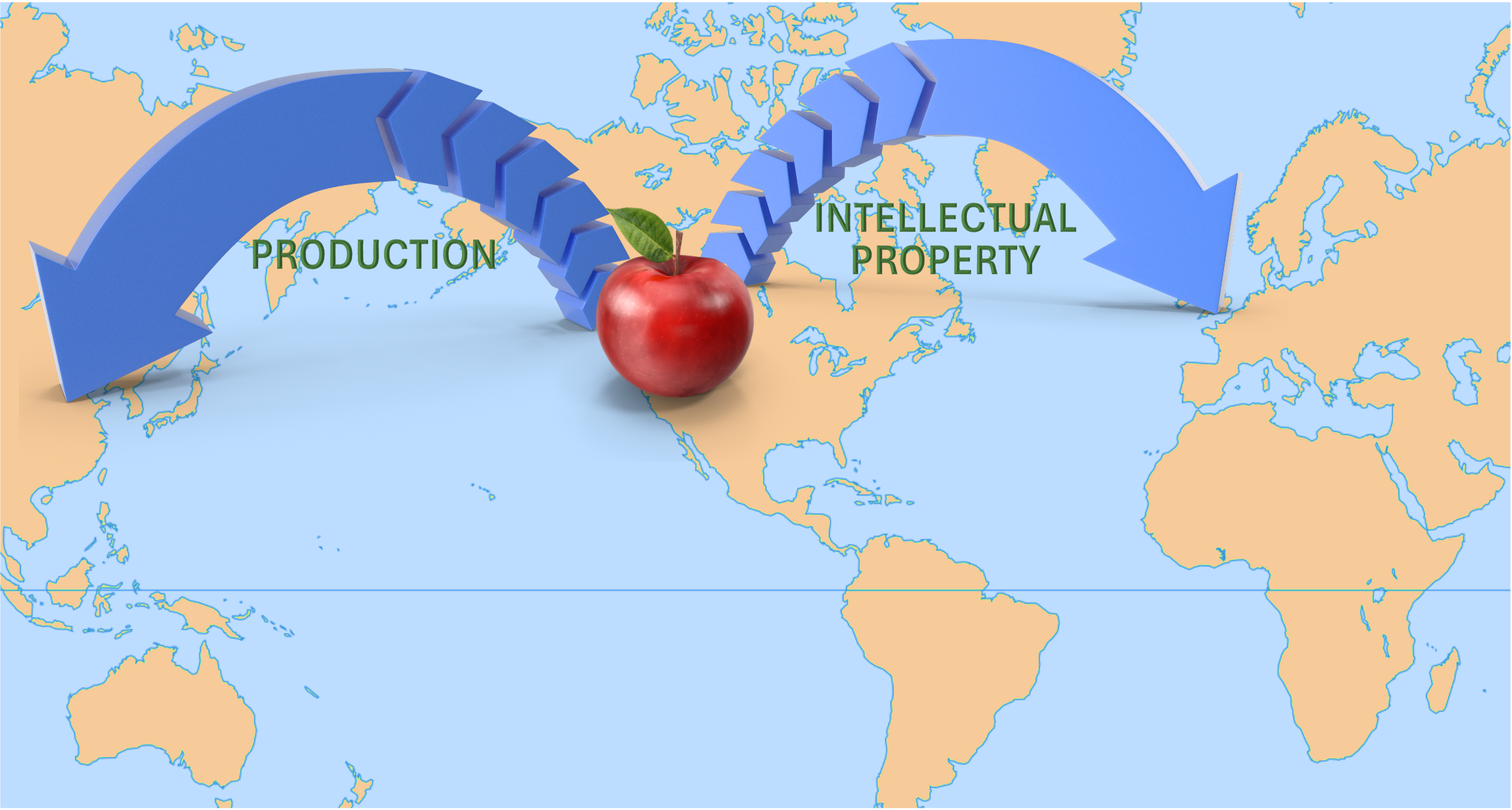

The United States has long been concerned about its persistent trade imbalance, frequently attributing responsibility to its business-partner countries for the gap between imports and exports. However, it should be recognised that most of the imbalance originates internally, driven by American corporations’ strategic pursuit of short-term profits, often through aggressive offshore profit-shifting practices. American businesses with the highest capitalisation, such as Apple, Google, and Microsoft, significantly contribute to this imbalance by establishing subsidiaries in low-tax jurisdictions like Ireland or Bermuda, legally diverting profits and depriving the US Treasury of critical tax revenues.

Apple has routinely utilised offshore structures, holding over $200 billion overseas at one point, strategically positioning intellectual property (IP) subsidiaries in countries with more favourable tax policies. Similarly, Google’s “Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich” facilitated the shifting of billions in global advertising revenue, resulting in minimal domestic taxation. These practices are typically legal yet ethically contentious, with annual corporate profit-shifting estimated between $300 and $350 billion, leading to approximately $100–$150 billion in lost US tax revenue each year, according to estimates from the Congressional Budget Office and economist Gabriel Zucman.

In addition to technology firms, professional service companies such as McKinsey, other consultancy firms, and numerous US law firms frequently establish regional offices overseas, ensuring substantial earnings remain offshore. Although these practices are mostly legal, they highlight the significant internal roots of the trade imbalance, reflecting structural issues in corporate governance and tax policy rather than external economic aggression.

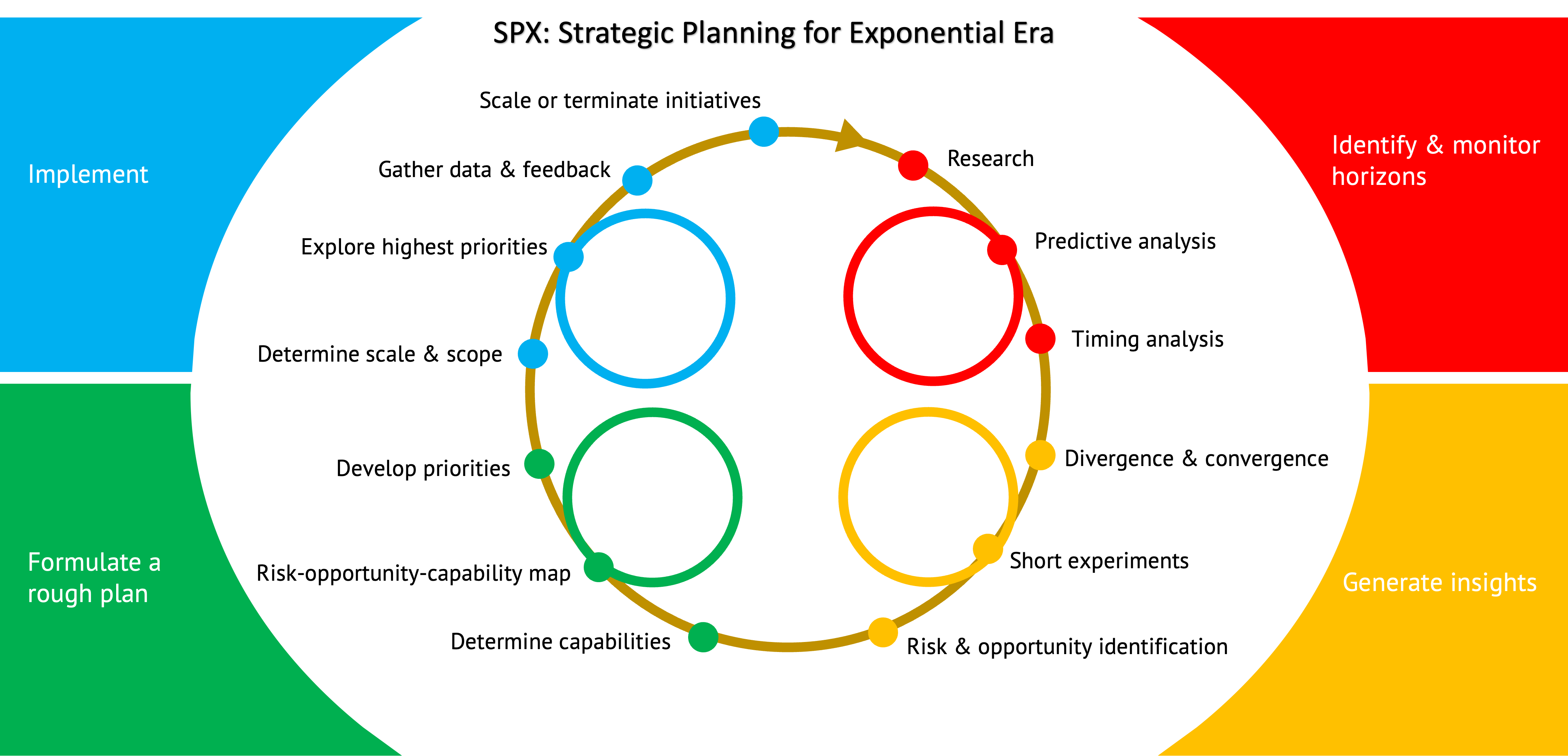

To meaningfully address these challenges, the US should initiate comprehensive internal reforms, beginning with corporate governance. A decisive shift from shareholder capitalism—prioritising quarterly profits—to stakeholder capitalism, where companies equally value long-term investments in employees, communities, and sustainability, is essential. The 2019 Business Roundtable statement was a symbolic step in this direction, but substantial action has been limited. True reform necessitates redefining executive compensation to incentivise sustainable, long-term growth rather than stock price manipulation through buybacks.

On the policy front, the US government should strengthen anti-profit-shifting measures by enhancing transparency through mandatory country-by-country financial reporting and enforcing stringent economic substance requirements. Implementing the OECD-backed global minimum tax (15%) could curb excessive offshore tax arbitrage by ensuring multinationals pay fair taxes irrespective of where they report profits. Additionally, penalising superficial offshore structures while incentivising genuine domestic investments could significantly mitigate revenue losses.

Ethically, American corporate culture should evolve to reject aggressive tax avoidance as standard practice. Promoting ethical standards and responsible business conduct, supported by public advocacy, investor pressure through Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria, and transparent financial disclosures, could substantially reshape corporate behaviour. Institutional investors, pension funds, and even individual consumers can wield considerable influence by rewarding ethical corporate actions and penalising short-termist, exploitative strategies.

Ultimately, resolving the US trade imbalance is not solely about external tariffs or punitive measures against other nations but requires confronting internal structural issues directly. By embracing rigorous regulatory reforms, incentivising ethical corporate governance, and committing to strategic long-term economic planning, America can effectively rebalance trade, recover significant lost revenues, and foster sustainable economic prosperity for future generations.