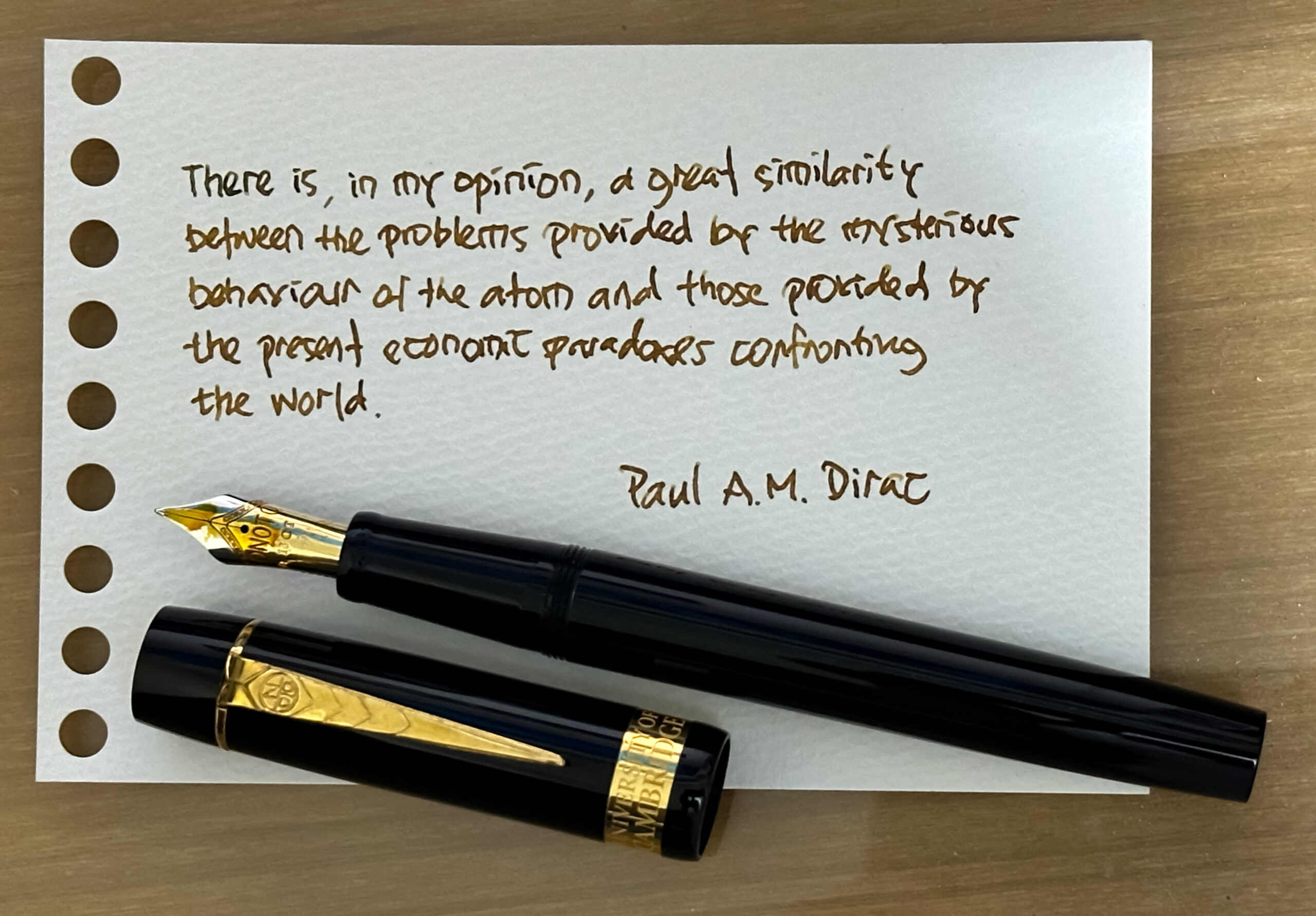

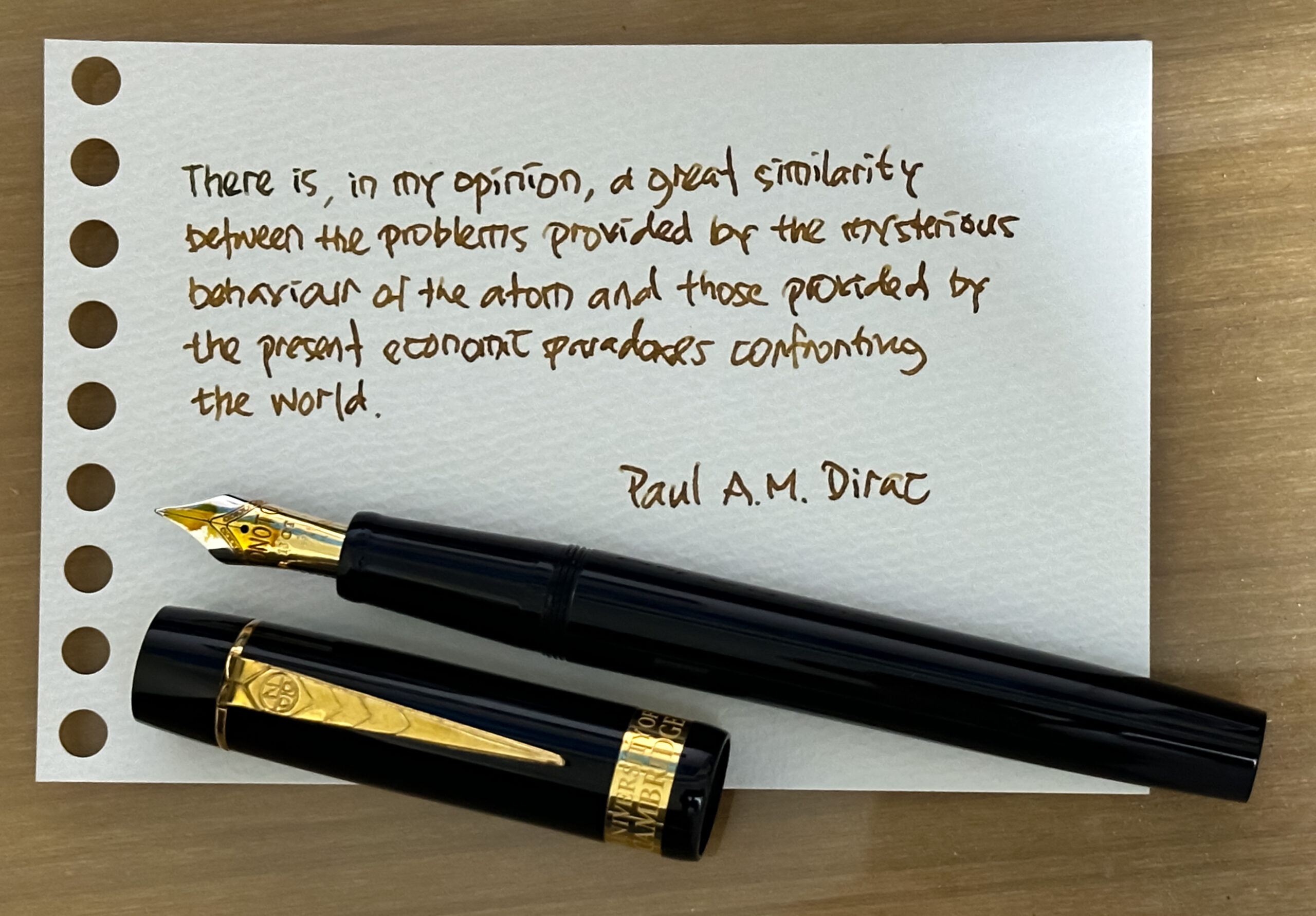

Yard-O-Led, a venerable British company rooted in the craftsmanship traditions of Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter, has held a distinguished place in the world of writing instruments since 1934. Originally known for its uniquely engineered mechanical pencils that ingeniously carried twelve three-inch leads—hence the name “Yard-O-Led”—the firm eventually turned its attention to fountain pens, marrying mechanical ingenuity with the aesthetics of classic British design. Every Yard-O-Led writing instrument remains a testament to artisanal precision, with each piece hand-assembled and meticulously hallmarked in accordance with the traditions of British silversmithing.

The Yard-O-Led Viceroy Standard Barley Fountain Pen is a shining emblem of this heritage. Crafted entirely in sterling silver, it upholds a lineage of British elegance and uncompromising quality. The Viceroy series, especially the Standard Barley variant, serves not only as a practical tool but also as a bridge to a bygone era, when fountain pens were objects of dignity and status. It contributes to the United Kingdom’s legacy of fine pen-making, standing shoulder to shoulder with other giants of European craftsmanship.

What sets the Viceroy Barley apart in the modern world of fountain pens is its deliberate refusal to bow to trends. It does not chase lightweight materials or space-age aesthetics; rather, it leans into the tactile and visual opulence of traditional silversmith work. The pen’s body is engraved with a Barleycorn guilloché pattern—an intricate diamond-shaped motif that catches the light in an understated yet captivating way. This engraving is not simply decorative; it enhances grip, balances reflection, and underscores the pen’s handcrafted nature. The pen’s clip is die-struck, not merely stamped, with a classic “YARD-O-LED” inscription.

True to its form, the Viceroy Barley is constructed of high-purity 925 sterling silver, a choice not made for mere ostentation. Sterling silver not only carries tactile warmth but also ages gracefully, developing a patina unique to the user—an intimate and evolving signature of ownership. British hallmarking on the barrel, including the sponsor’s mark “YOL”, fineness marks, and assay office insignia, confirms its authenticity and ties it to a centuries-old tradition of precious metalwork.

The nib is an 18ct gold unit, plated in rhodium for durability and aesthetic harmony with the silver body. It is engraved with the Yard-O-Led scrollwork motif, echoing the symmetry and flourish of vintage British design. The nib featured here is a Fine (F) size, offering a precise and consistent line, ideal for both personal writing and formal correspondence. Smooth yet firm, it balances expression with control, much like the pen itself—a dignified blend of subtle luxury and mechanical clarity.

In the realm of contemporary writing instruments, the Yard-O-Led Viceroy Barley is less a competitor and more a category unto itself. It is a pen for those who value tradition, tactile beauty, and a deliberate pace. One does not rush through prose with such a pen; one composes. Each stroke is a continuation of legacy, and in an age of disposability, that is nothing short of revolutionary.